Removing fences, reintroducing herding: how the redomestication of cattle may lead to wilder landscapes

by Wisse van Engelen

The picture above shows a common sight in Botswana. Cattle are often seen straying along roads, as well as in towns, through villages, and in the bush. When I first came to Botswana for my fieldwork I was surprised to see cattle everywhere, but I soon became accustomed to it. I also learned that stray cattle permeate many aspects of life, including road safety, disease control and human-wildlife conflict. But where do these cattle come from? And why would farmers let their cattle stray?

In one study conducted in Habu, a village in the north-west of Botswana, it was found that the main cause of livestock loss is farmers losing their livestock (i.e. not knowing where they are) rather than the livestock being killed by predators or lost to disease (issues that generally receive a lot more attention) (Heermans, 2022). In and around Habu, as in many other communal rangelands in Botswana, many farmers keep their cattle in a kraal at their cattle post during the night, but leave the animals to roam freely during the day. In some cases, the cattle return in the evening to be kraaled again, but sometimes the cattle do not. Sometimes the cattle do not return for a few days or weeks. And sometimes they do not return at all, and are nowhere to be found. Whereas farmers used to have their cattle herded (either by themselves, their children or employed herders), nowadays the practice of herding has largely disappeared. The main reason for this – as told by elderly farmers from Habu – is that their children are not able to help with herding anymore since Botswana’s introduction of compulsory schooling in the 1960s.

But today there is an initiative to reintroduce the herding of cattle – in Habu, as well as in another dozen sites across Southern Africa. The initiative, a programme called Herding 4 Health (H4H), trains local community members as professional herders – or what the programme calls ‘ecorangers’. They do not only herd their own cattle, but also the cattle that has been entrusted to them by other farmers from the community. In this way, they can take care of the community’s cattle without the need for a herder for every single farmer.

While one might expect the programme to be spearheaded by rural development actors, this is not the case. Rather, the H4H partnership has been founded by Conservation International and the Peace Parks foundation: two big international conservation organizations. Commonsensically we would think that these organizations have the mandate to protect, maintain and restore the wild. Why are they now involved in the redomestication of cattle?

Multispecies literature can help us answer this question. In Domestication Gone Wild, multispecies scholars Swanson, Lien and Ween (2018) revise the prevailing understanding of domestication as bringing a single wild species into the realm of culture. As they argue, domestication involves more than a single species. The domestication of salmon, for example, has far-reaching effects. Firstly, along with salmon, salmon farmers have started to domesticate wrasse – a fish species that feeds on sea lice and can thus help keep the salmon clean from infections. Secondly, salmon can escape and then go on to hybridize with wild salmon, affecting regions far beyond the farm. And thirdly, there’s feed. The fish meal that salmon eat is made from fish whose removal from the ocean restructures food webs and other ecological relations, possibly setting off various chain reactions. These different effects show that many more species than only salmon are involved in their domestication. As such, Swanson and her colleagues argue, domestication may be better understood as a reconfiguration of multispecies assemblages.

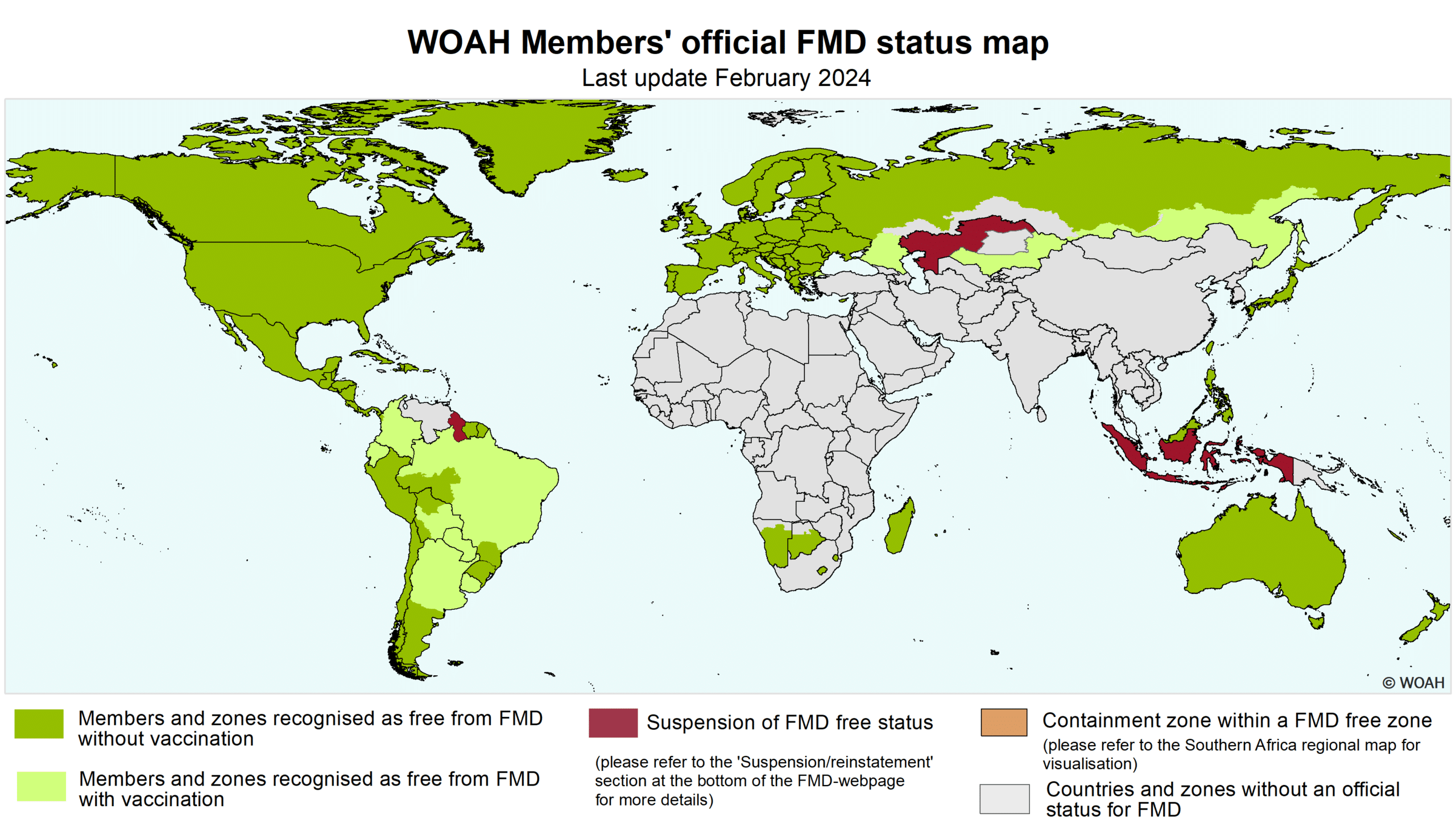

Through this multispecies lens we can see that the domestication of cattle in Botswana goes beyond the transformation of cattle only: it changes predator, rangeland, human and disease ecologies. Firstly, predators will have a harder time finding a tasty cow when cattle are herded. As for the rangelands, grasses will be grazed differently with controlled movement. Also, farmers and their families will be more inclined to move to villages or towns rather than stay at their cattle post when their cattle is kraaled with the communal herd. And with regard to diseases, pathogens will struggle to jump species when the cattle are herded and not coming into contact with disease-carrying wildlife such as buffaloes. In these various ways, H4H reconfigures multispecies assemblages.

The reintroduction of herding affects relations between cattle and (i) predators, (ii) pastures, (iii) people, and (iv) pathogens (photos taken by author).

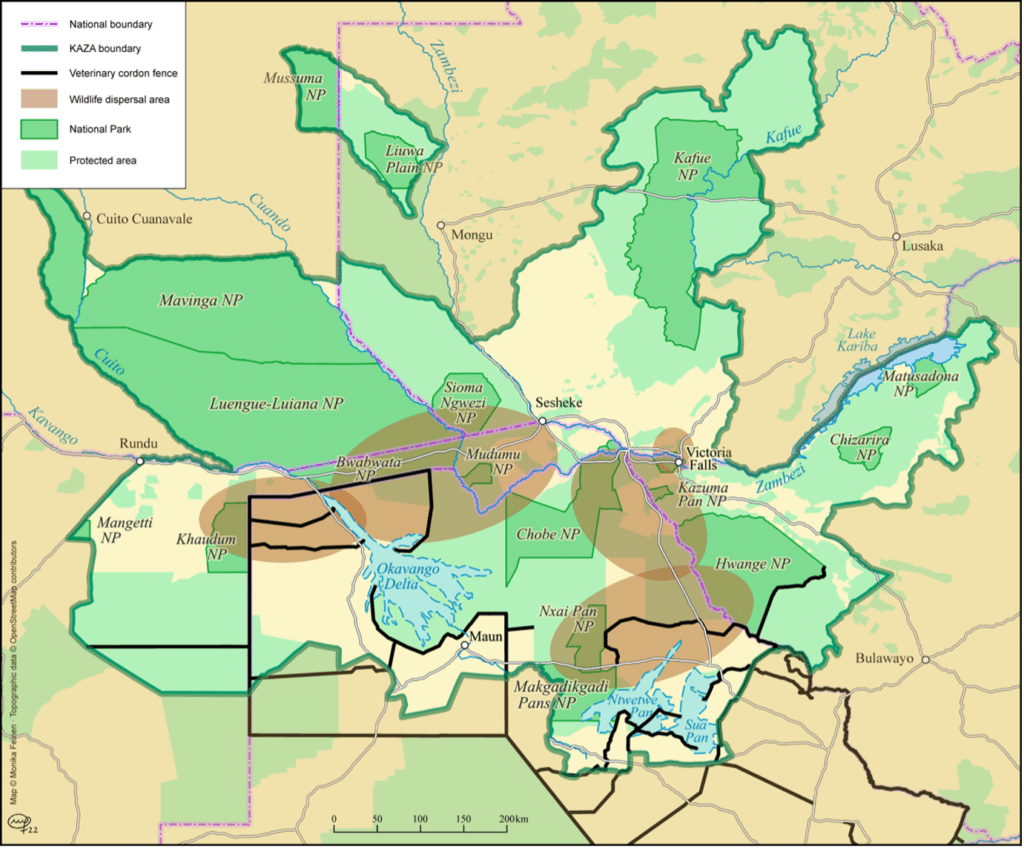

For conservation organizations, particularly the avoidance of pathogen transmission is an important outcome of herding. They argue that herding can replace some of the thousands of kilometres of fencing that currently aim to control cattle and buffalo movement in Botswana (see map below). These fences are one of the main challenges to realizing the vision of a large connected conservation landscape in the wider region, as they do not only obstruct the movement of pathogens and their hosts, but also many non-target wild animals. Replacing these hard barriers with a strategy based on herding allows for more place-based and responsive management of movement and can restore the natural processes of wildlife migration and dispersal.

Where the reintroduction of herding in Botswana thus seemingly only transforms human-cattle relations, a multispecies lens reveals that this transformation extends much further. Herding reconfigures multispecies assemblages and drives landscape changes, potentially across national borders. At the same time, the case of redomesticating cattle in Botswana reveals something to multispecies studies too. Because unlike the case with the salmon, the case of cattle here shows that domestication can involve not only control but also freedom. As shown, the domestication of one species may mean the (possibility of) rewilding for others.

Veterinary fences in the Kavango-Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area (map produced by Monika Feinen).

References

Heermans, B. (2022). A One Health assessment of a Herding for Health project at the wildlife-livestock interface in western Ngamiland, Botswana. (PhD thesis). University of Pretoria, Pretoria.

Swanson, H. A., Lien, M. E., & Ween, G. B. (2018). Domestication gone wild: politics and practices of multispecies relations. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.