Rewilding for whom? Coexisting with wildlife against the biodiversity crisis

by Léa Lacan & Michael Bollig

Wildebeests in the Simalaha conservancy (Zambia) – Picture by Léa Lacan 01.04.2023

Globally wildlife abundance decreased by 58% only between 1970 and 2014. A few entries on the African continent must suffice to illustrate the doom scenario. A World Bank communication estimates that climate change alone will result in the loss of over half of African bird and mammal species by 2100. Other major drivers of biodiversity decline include the pollution of ecosystems, the proliferation of invasive species and the overexploitation of natural resources. Agricultural intensification and expansion of land use both conditioned by increasing agro-industrialization and growing population numbers lead to the loss and fragmentation of habitats, further disrupted by violent conflict and extractivist strategies. 2

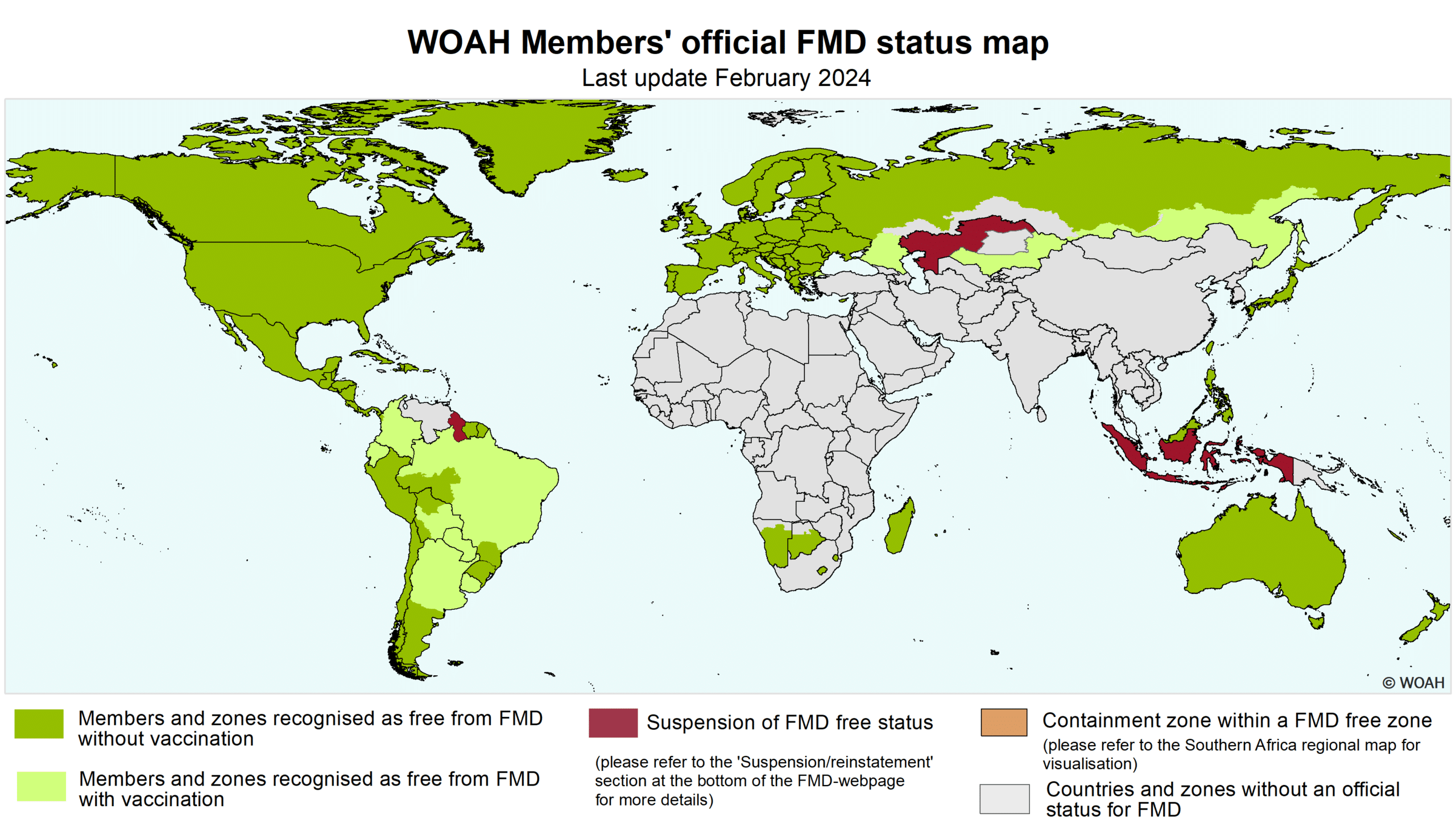

In response to the global biodiversity crisis, the UN called last year for placing at least 30% of the world’s land under a conservation status by 2030.3 This necessitates the increase of conservation areas by about 10 per cent within a decade: a highly ambitious goal.

Africa has been coined the “Conservation Continent” and stands at the forefront in the establishment of conservation areas of many types. It is very likely that major parts of the required expansion of protected lands in the 2020s will happen in Africa. Indeed, the continent shows a rich diversity of innovative conservation models, that involve rural people in different ways, while still more traditional approaches of “fortress conservation” prevail. The Kavango-Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area (KAZA TFCA) is a striking example of this inevitable proximity of fortress conservation and community-based approaches. As the world’s largest transboundary conservation area, its 520,000 km2 extend over five national territories (Namibia, Botswana, Zimbabwe, Zambia, Angola), and covers 371,394 km2 of land under conservation.4

This includes 19 national parks, combined with other types of conservation areas as varied as community conservancies, protected governmental and community forests, game or nature reserves. Yet, KAZA is not only a conservation landscape, it is also the home of 3 to 3.5 million people, most of which depend on rural livelihoods based on the access to natural resources.

The call to extend conservation areas globally is coupled with the urge to respect the rights of indigenous people and rural communities, and to work with, not against the local population. Yet, conservation for those living in conservation areas often means a loss of access to land and resources, as well as an increased presence of wildlife feeding on people’s crops, and threatening their livestock through contagious diseases, predation, or competition for grazing. What does conservation really mean for those who are living in landscapes in which wildlife and nature protection becomes the priority? Is coexistence with wildlife possible or even desirable? And if so, for whom? And most importantly: who decides what is protected, how it is protected and how benefits and damages accruing from conservation efforts are distributed across stakeholders who act at different scales, from local small-scale farmers to employees of large international conservationist NGOs? These nagging questions bring us quickly to the issue of environmental justice and its three dimensions of recognition, procedural and distributive justice. 5

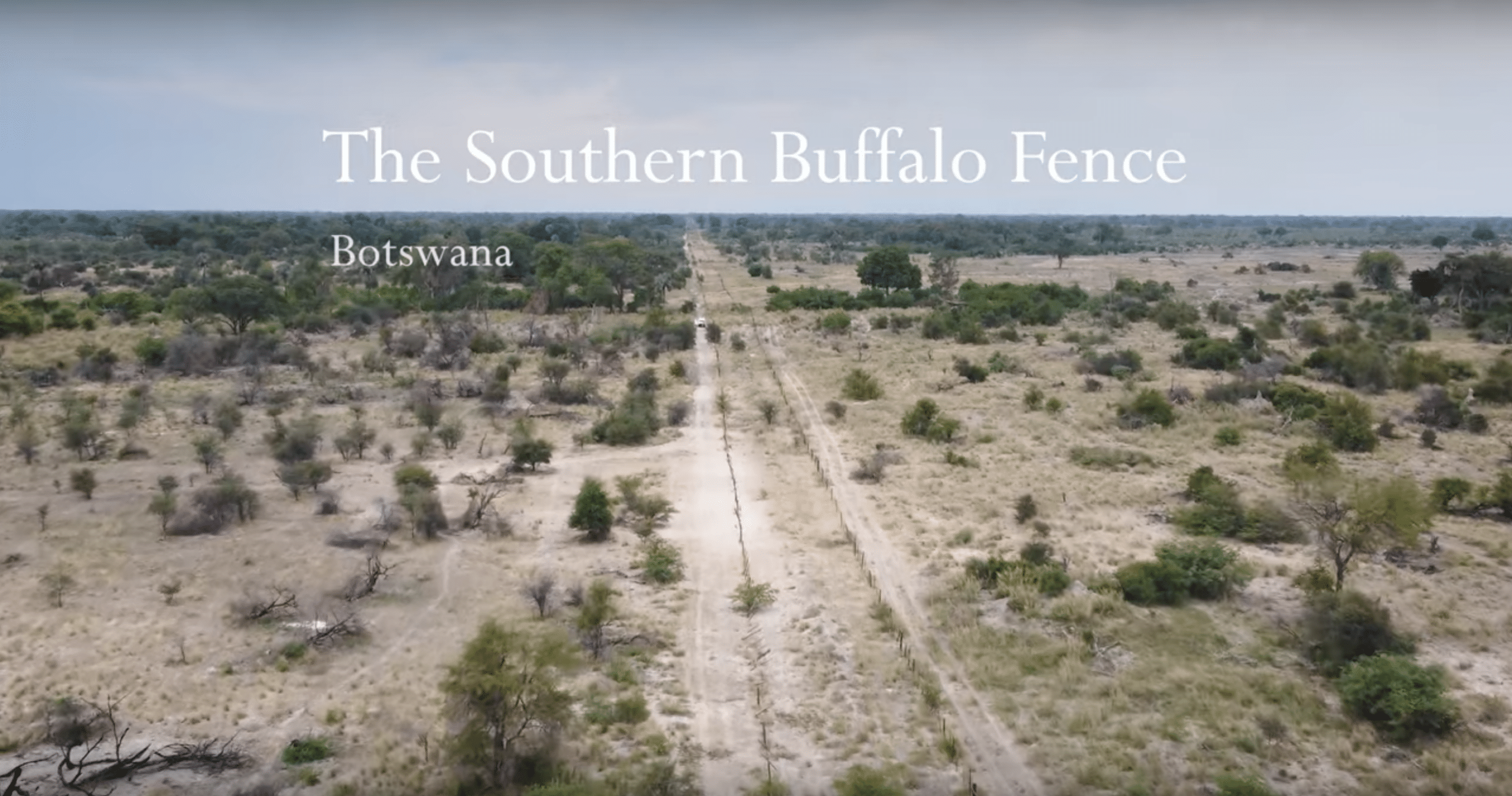

Within KAZA, numerous attempts have been made to make conservation more community-based, and to couple conservation goals with livelihood resilience and poverty alleviation. Conservancies in Northern Namibia have been quite successful in developing tourism to trigger revenues, with significant incomes accruing from trophy hunting.6 Conservancies and wildlife management areas also offer opportunities for programs targeting the development of rural livelihoods to take place, e.g. through conservation agriculture, aiming at improved and sustained crop production on smaller surfaces. The Simalaha conservancy in south-western Zambia, for example, reintroduced wildlife species in settled areas. It aspires to put much emphasis on supporting sustainable agriculture and fisheries at the local level, as a pendant for conservation, in order to strengthen acceptance among local farmers.

Yet, despite all these efforts, benefits from conservation and their distribution at the local level are still unclear. National governments, non-governmental organizations, or local traditional leaders set conservation as a priority, but it is the local inhabitants in conservation areas who have to live with these decisions. They are the ones who have to coexist with wildlife. Yet, it is often not their own initiative, and, even if they are consulted in most cases, their agency in defending their own agenda, and in taking the decisions that impact their own lives, is questionable. Moreover, opinions on the role of conservation in rural development are often diverse within a community, making the search for a consensus time intensive and conflictual.

Can coexistence be successful, if not fully decided and driven by the ones who are the first concerned? Because conservation implies deep and radical changes in the lives of the local inhabitants, its design and implementation have to be holistic with the aim to contribute to environmental justice and sustainability at the same time: it is a question of land use, of natural resource management, but also of local economic development, cultural self-determination and political representation. Therefore, conservation areas have the potential to become sites for the experimentation of new democratic processes at the local level. Bringing different actors together – national governments, international donors and technical assistance, local leaders and local inhabitants – conservation areas should become an enabling environment for the development of local initiatives and representation. They have the capacity to open new political spaces for negotiating the conditions of coexistence between people, livestock and wildlife locally. COP 15 at Montreal and the Kunming Protocol (if this is the name it is going to adopt as a follow up to the Nagoya Protocol) must contribute to that end and must provide strategies, spaces and funds to harmonize conservation goals and environmental justice.

Footnotes

- https://www.un.org/sg/en/content/sg/statement/2022-09-20/secretary-generals-video-message-countdown-cop15-leaders-event-for-nature-positive-world

- Bollig, M. 2022 “Twenty-First Century Conservation in Africa: Contemporary Dilemmas, Future Challenges.” African Futures, edited by Michael Bollig et al., Brill, 2022, pp. 111–24. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1163/j.ctv2kqwzjh.16.

- https://www.iucn.org/resources/issues-brief/post-2020-global-biodiversity-framework

- Stoldt, M., Göttert, T., Mann, C. et al. Transfrontier Conservation Areas and Human-Wildlife Conflict: The Case of the Namibian Component of the Kavango-Zambezi (KAZA) TFCA. Sci Rep 10, 7964 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-64537-9

- Schlosberg, D. (2012). Climate justice and capabilities: A framework for adaptation policy. Ethics & International Affairs, 26(4), 445-461. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0892679412000615

- Kalvelage, L., Revilla Diez, J., & Bollig, M. (2022). How much remains? Local value capture from tourism in Zambezi, Namibia. Tourism Geographies, 24(4-5), 759-780; Gargallo, E. (2015). Conservation on contested lands: the case of Namibia's communal conservancies. Journal of Contemporary African Studies, 33(2), 213-231; Bollig, M. & E. Olwage. 2016. The Political Ecology of Hunting in Namibia’s Kaokoveld: From Dorsland Trekkers’ Elephant Hunts to Trophy-Hunting in Contemporary Conservancies. Journal of Contemporary African Studies 34(1). 61–79.